前德國駐華大使陶德曼藏畫

From the Collection of Dr. Oskar Paul Trautmann, Former German Ambassador to China (Lots 3193-3202)

Trautmann and his wife, 1936

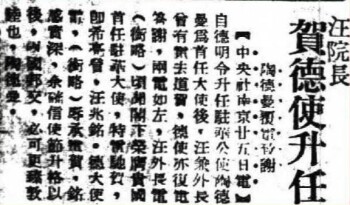

陶德曼博士(Dr Oskar Paul Trautmann,1877-1950),德國資深外交家。早歲習法,畢業後入外交部,在一九○七年至二五年間先後獲派駐聖彼得堡、神戶,曾任駐日大使助理及臨時代辦。一九二六年返柏林,在外交部主管東亞事務。一九三一年十月,獲派往北平出任駐華公使。一九三五年五月,德使館升格為大使館,遂轉往南京,被任命為首任德國駐華大使,直至一九三八年八月抗日戰爭全面爆發後離華。

陶德曼在近代中德關係史中地位舉足輕重,為促進兩國友好貢獻良多。他在二十年代末來華前已參與對華事務,時國民政府面對日本步步進逼之野心,力圖加強國防自衛,德方則需穩定供應之原材料,雙方遂成合作伙伴,由德方組軍事顧問團來華協助軍隊現代化,並出售軍事裝備及工業用品,中方亦大量出口鎢砂等原材料予德,此緊密關係一直維持至一九三八年方止,陶德曼即為此段期間雙方交涉之要員。駐華期間,他與國民政府要員往來密切,一舉一動皆具影響力,每二三日即在報刊上見其人其事,呈遞國書、會議、演講、出遊等。在一九三七年抗日戰爭之始,兵戎相見,在此關鍵期間,他從中斡旋以促成和平,此為中國近代史上著名之「陶德曼調停」,雖最終談判未果,倘若成事,或可扭轉時局,改寫歷史!

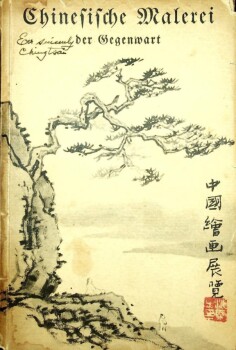

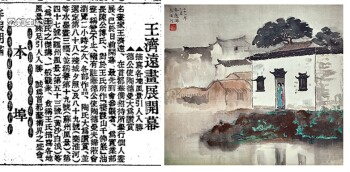

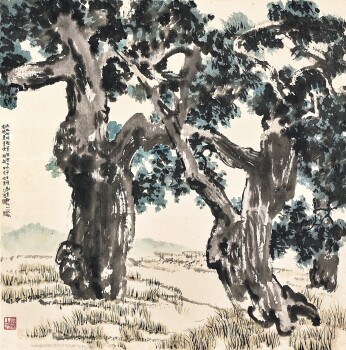

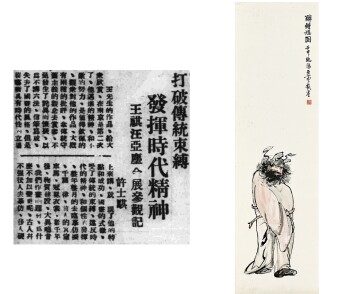

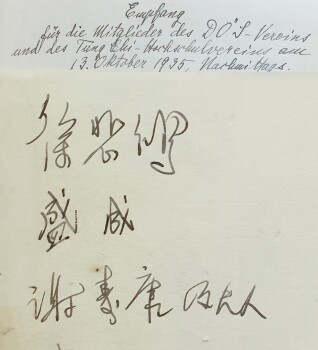

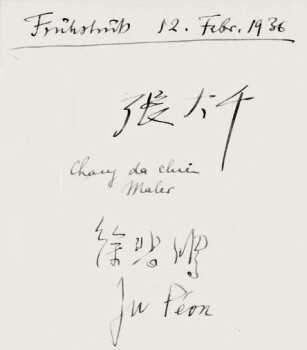

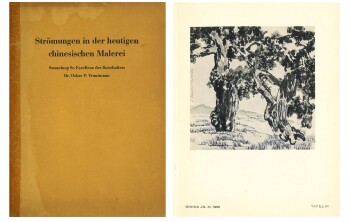

陶氏熱愛中華文化,積極推動兩國文化交流。一九三三年,他擔任剛成立之中德文化協會會長,翌年初柏林舉辦〈中國繪畫展覽〉,展出作品逾二百七十幅,他即活動推手之一。公餘之暇,嗜好藝術,與不少畫家如徐悲鴻、齊白石、張大千等交流,入藏書畫逾一百五十幅,多直接得自畫家或購自畫展,部份具其上款。其搜求範圍集中當代畫家,不分地域門派,非專嗜某家畫風,或以西方口味為主導。他熟讀蔣彝〈中國畫論〉、林語堂〈吾國與吾民〉等,在其洋洋千字演講稿辭中,從宗教、哲學、文化、歷史、詩詞不同方面深入剖析中國畫,如筆法、章法、意境、佈局之重要性,以至造化自然、隱逸避世之思想等,了解透徹,非流於泛泛空談。一九三六至三八年間,他往來中德兩地,在德國法蘭克福、柏林、克雷費爾德、布雷斯勞先後舉辦畫展,展出其個人藏品及國家博物館收藏逾百,又刊展覽圖冊,讓德國觀眾「從中國思想、中國感情作出發點,來觀察中國畫,以求認識永在的真美……其間總避免以本人一己的意見去替代中國人對於他們繪畫的意見」。陶德曼一九三八年歸國後,未再踏足中國,惟其所藏之青銅器在翌年輯印成〈使華訪古錄〉一書,由輔仁大學出版,可見其收藏範圍之廣。

其部份藏品在二戰時散失,餘者留付後人,珍藏至今。本輯皆其孫輩承襲者,大部份在三十年代德國展覽中露面,沉潛多年,今再面世,堪作中德兩國文化交流之歷史見証!

Dr Oskar Paul Trautmann (1877-1950) was a senior German diplomat. Having studied law at a young age, he joined the Ministry of Foreign Affairs after graduating. From 1907-25 he was first stationed in Saint Petersburg, before acting as assistant to the ambassador to Japan and a chargés d'affaires ad interim in Kobe. In 1926 he returned to Berlin and was put in charge of general affairs in East Asia at the foreign office. He was then delegated to Beijing in October 1931, stationed in China to take up the post of minister. In May 1935, the German consulate was promoted to an embassy and he was transferred to Nanjing, where he was appointed first German ambassador to China, a post he held until he departed China in August 1938 when the Second Sino-Japanese War was in full swing.

Dr Trautmann holds a crucial position in the history of recent Chinese-German relations, contributing greatly to improving diplomatic affairs between the two nations. He had already participated in affairs with China in the late 1920s before his arrival in the country. The Nationalist Government at the time was facing the steady advance of Japanese pursuit and were striving to strengthen their national defence, while the Germans needed a stable supply of raw materials. Thus, the two sides formed a friendly partnership. The Germans organised a military advisory group to assist in the modernisation of the Chinese army, and sold them military equipment and industrial supplies, while the Chinese exported large amounts of raw materials, such as Tungsten ore, to the Germans. This close relationship was maintained until 1938 and was only possible because of Dr Trautmann, who played a key role in the negotiations between the two sides throughout this period. During his time stationed in China, he remained in close contact with Chinese government officials and was heavily influential, appearing in the press every two, three days for his various appearances, such as when presenting letters of credence, attending conferences, giving lectures and sightseeing. When the Second Sino-Japanese War broke out in 1937, the Chinese and Japanese met with open hostility. During this crucial stretch, Dr Trautmann acted as an arbitrator to facilitate peace, famously known in recent Chinese history as the “Trautmann Mediation”. Although these talks eventually amounted to naught, if they had succeeded, they could have reversed the unstable political situation and completely rewrote history!

Dr Trautmann had an ardent love for Chinese culture, enthusiastically promoting cultural exchanges between the two countries. In 1993, he served as chairman of the newly established Sino-German Cultural Association. He was also an active promoter of the “Chinese Paintings Exhibition” held in Berlin early the following year, where over two hundred and seventy paintings were displayed.

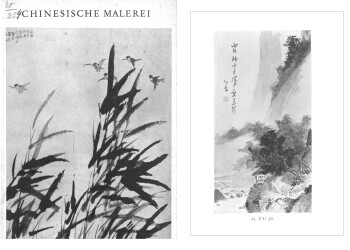

In his free time, he was an art hobbyist, interacting with numerous artists such as Xu Beihong, Qi Baishi and Zhang Daqian. His collection consists of over a hundred and fifty paintings and calligraphic works, many of which were obtained directly from the artists or purchased at art exhibitions, with some even stating his name as the recipient on the painting. Dr Trautmann mainly sought after the works of contemporary artists and was indifferent to regional schools of thought. He did not have a specific bias towards a certain style of painting, nor did he judge the art by Western standards, even familiarising himself with texts such as Chiang Yee’s “The Chinese Eye” and Lin Yutang’s “My Country and My People”.

In one of his impressive speeches, he thoroughly dissected Chinese paintings from the perspective of religion, philosophy, culture, history and poetry, analysing the importance of calligraphy, composition, artistic ambience and overall presentation so that even abstract concepts such as creating nature or retreating from the world can be understood in full.

From 1936-38, he travelled back and forth between China and Germany, successively holding exhibitions in Frankfurt, Berlin, Krefeld and Breslau, displaying over a hundred works from his personal collection and the National Museum. He also published exhibition catalogues so that German audiences could “observe Chinese art whilst bearing in mind the thoughts and feelings of the Chinese people, in order to fully comprehend its eternal beauty… At the same time, it prevents their personal Western perceptions from displacing Chinese people’s opinions towards their own art”.

After returning to Germany in 1938, Dr Trautmann did not set foot in China again. Unfortunately, parts of his collection disappeared in World War II, while the remainder has been passed on to future generations, carefully stowed away to this day. The works in this collection have all been inherited by his grandchildren and most were displayed in German exhibitions in the 1930s. Having been hidden away for many years, they will finally resurface today, serving as historical evidence of the interaction between Chinese and German culture!

Qi Baishi particularly liked amaranth, which turns red with frost as autumn approaches. It is often featured in his paintings and he even wrote poems praising it. Amaranth is also known as “Lao Laihong” in Chinese, which directly refers to its colour changing properties with the passing of time, where it gains its famous reputation from. An additional meaning of health and longevity can also be derived from the plant’s rosy complexion.

This painting is filled to the brim with red leaves, coloured with rouge and cinnabar, with the varying intensity of pigments revealing the various changing layers of brightness and darkness. The lines are lucid and the colours vibrant, creating a stark contrast to the black ink of the inscription. The painting lacks any depictions of grass or insects since, according to Ma Bi (1912-1985), “Qi Baishi expressed at one point that he temporarily stopped grass-and-insect paintings. This was because Dr Trautmann, the German ambassador, once thought that one of such paintings he purchased in Beijing was done by someone on behalf of Qi, rather than his own original work.” Ma and Qi are from the same village, with both families maintaining a strong friendship spanning four generations. As such, the assertion is not a hollow statement. Usually, paintings with a similar subject matter would be supplemented by a mantis. Yet, perhaps because of the story mentioned above, such features have been deliberately minimised in the works gifted to Dr Trautmann, such as the case with the painting of red plums that lack any embellishments of bees in his collection. Nevertheless, the painting at hand is not dated, yet it can be assumed that it was completed in the early 1930s based on the address of “minister”, since Dr Trautmann took up the post of ambassador in 1935.