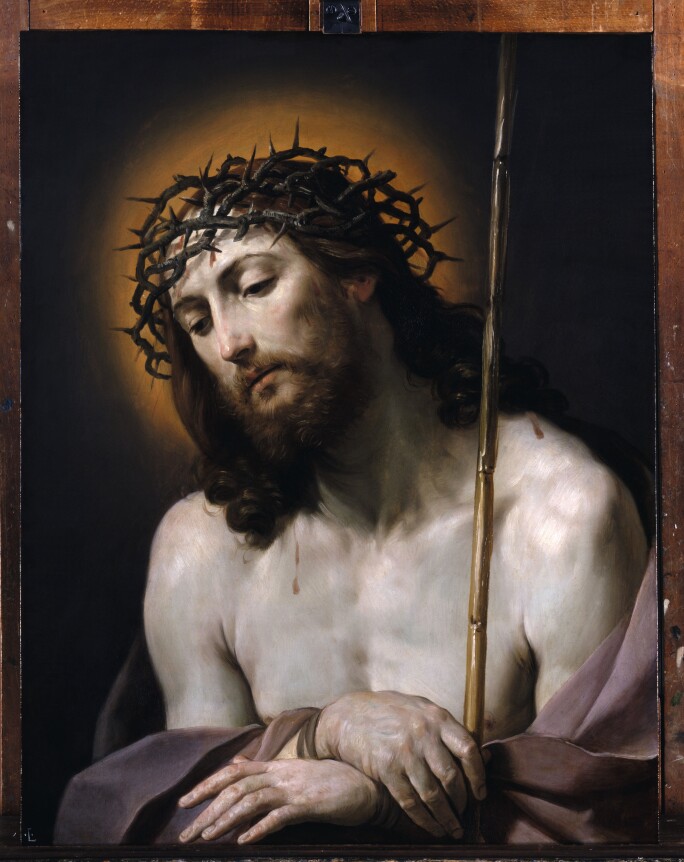

The image of the bound and bleeding figure of Christ as he was presented by Pilate to the people has been one of the most powerful images in Christian art ever since the Renaissance, but never more so than in the paintings of Guido Reni, one of the greatest and most influential of all Italian seventeenth century painters. Painted in the late 1630s this moving image exemplifies the unique combination of grace and religious conviction that he brought to his depictions of the suffering Christ. An extremely devout man himself, in works such as this Reni concentrated less upon the outward physical pain of Christ than His inner spiritual agonies, and in the process brought to his subject an intensity and graceful beauty that has informed Catholic imagery of the Passion ever since. They remain to this day among the most famous and recognizable of all his paintings.

This picture is one of a small group of paintings on the theme of Ecce Homo that Reni painted towards the end of the 1630s, all of broadly similar size and format. In them the figure of Christ is shown bust-length against a plain background wearing the crown of thorns and holding a reed scepter, both symbols of kingship given to him by the soldiers mocking him in his captivity. His hands are bound by rope, and his shoulders draped with a simple cloak. The closest parallels are to be found with two paintings, one on copper and the other on canvas, both in the Gemäldegalerie in Dresden.¹ In that on copper (fig.1), the reed scepter is similarly positioned vertically, but Christ’s head faces to the left and faces downwards instead of upwards, giving the work a more introspective mood. Another version, unknown to Pepper but which is closely related to the Dresden copper, and in which Christ’s hands rest upon a plinth, was sold New York, Sotheby’s, 29 January 2015, lot 37. The angle of the head and the cast of the eyes are more comparable in the version in Dresden that is on canvas (fig.2), although the head now inclines to the left rather than to the right, and the reed scepter is placed across Christ’s chest instead of resting against his shoulder as in the present canvas.

In his 1984 catalogue of Reni’s paintings, Stephen Pepper dated both the Dresden versions of the Ecce Homo to circa 1636-7 and proposed a ‘slightly later’ dating for the present canvas on the basis of photographs. Dr. Andreas Henning, Curator of Italian Paintings at the Gemäldegalerie in Dresden, also dates the Dresden copper to around 1636-7.² Given the very close parallels in both style and format between this and the other versions of the composition it seems reasonable to suppose that they were all painted within a short space of time of each other. The present canvas may therefore come just after the Dresden works but before those generally assigned a slightly later date around 1639-40, such as the oval Christ crowned with thorns in the Louvre in Paris, or the largest of the whole series, the famous half-length Ecce Homo in the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge. Such a dating is also evident in the style of the painting itself, which reflects Reni’s change from the early 1630s onwards from his earlier high coloring and careful brushstrokes to a much lighter almost silvery palette, in which the paint is more thinly applied and the forms less detailed. Here the paint is confidently and fluently applied throughout, with evident signs of pentimenti to be found in the crown of thorns, which are also clearly visible under infra-red reflectography (fig. 3). In contrast to the golden glow of his aureole Christ’s body is painted in the palest of tones. His cloak is rendered in a delicate almost transparent shade of lilac similar to the pinks of his flesh, and the cords at his wrists are brushed in the palest tones of silver-blue and grey.

In the design of this and related works Reni may well have been mindful, as Richard Spear has observed, of famous precedents such as Titian’s own version of the subject painted around 1558-60 today in the National Gallery of Ireland in Dublin, or Albrecht Dürer’s famous full-length drypoint of 1512, but his interpretation brought a new sense of pathos to the subject. Reni’s personal piety and faith is well documented by his contemporaries; his biographer Carlo Cesare Malvasia (1616-1693), for example, records his daily attendance at Mass and his particular devotion (‘devotissimo’) to the Virgin Mary³ and from his earliest years his religious paintings were always concerned with intense emotion, framed within his aesthetic notions of classical beauty and form. Nowhere was this more apparent than in his portrayals of the Virgin Mary and her Son. Here, the physical traces of Christ’s bloody ordeal are largely eschewed in favor of an image which concentrates instead upon his spiritual or psychological suffering. Reni’s paintings such as this offered a readily understandable pictorial representation of the duality of the spiritual and the historical or human Jesus: while recognizably divine, Reni’s unadorned images of the suffering Christ as a man remained immediate and personal for the faithful viewer. The success of what was virtually a new genre was remarkable and Reni was quickly obliged to produce such subjects in multiple versions to meet the demand for them. Although their impact has been somewhat lessened by numerous studio replicas and copies – many no doubt occasioned by Reni’s notorious gambling debts - they are among the most recognizable and iconic of all Christian images, and have remained so for the Catholic faithful and many others for over three hundred and fifty years.

The early history of this painting is unfortunately not known.⁴ In the eighteenth century it formed part of the celebrated collection of Count Gustav Adolf Sparre (1746-1794) in Sweden (fig.4). Sparre came from a very wealthy background; his father Count Rutger Axel Sparre (1712-1751) was a Director of the Swedish East India Company, whose marriage in 1740 to Sarah Christina Sahlgren (d.1766) brought further fortune to the family dynasty. Sparre’s collection was largely acquired on his Grand Tour in the Low Countries, England, France and Italy between 1768-1771 and 1779-80. Numbering 108 paintings in all, the collection was chiefly comprised of works by the leading Dutch and Flemish painters of the seventeenth century, the most famous of which were two Rembrandts, a late Portrait of a young man today in the National Gallery of Art in Washington, and the oval Portrait of a man of 1632 now in a private collection in the United States.⁵ His predilection was, however, very markedly for smaller cabinet pieces, including several works by David Teniers, as well as others by Philips Wouwerman, Gabriel Metsu and Jan Steen. The majority of these were hung in the Sahlgren-Sparre Palace in Gothenburg. It is not known exactly when Sparre acquired the Reni, but this was most probably on his Grand Tour between 1768 and 1771, perhaps in Paris, where he had sat for his portrait to the Franco-Swedish painter Alexandre Roslin (1718-1793). The Guido Reni formed part of a much smaller group of Italian works, but it too was kept in Gothenburg as one of the fifty-six works that hung in the Blue Drawing Room, rather than sent to the family’s country residence at Kulla Gunnarstorp, where most of the Italian and French pictures were hung. Remarkably the Sparre collection would remain almost entirely intact for the next two hundred years, until a large part was sold in 2007.⁶

1. Inv. nos. 329 and 330. Copper, 76 x 60 cm., and canvas 79 x 65 cm. respectively. Pepper 1984, pp. 274-5, nos. 161 and 162, reproduced plates 186 and 187 (plates incorrectly transposed). The author surmised that the former had been destroyed during the war when it had in fact been returned to the gallery in 1974. See also H. Marx (ed.), Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister Dresden, Cologne 2005, vol. II, p. 427, nos. 1454 and 1455, both reproduced. The paintings were bought separately and entered the collections in Dresden at different dates in the mid-eighteenth century.

2. Although at the time of the 2006 sale Dr. Henning dated the Dresden copper around 1640 (private communication), he later revised this in favor of an earlier dating of 1636-7. See A. Henning, “The new technique of oil on copper,” in Captured Emotions: Baroque Painting in Bologna, exh. cat., Los Angeles 2009, p. 27.

3. C.C. Malvasia, Felsina Pittrice: Vite de Pittori bolognesi, 1768 (Bologna 1971 ed.), pp. 388, 397-8.

4. Among untraced versions of this subject mentioned in early sources are a ‘Cristo incoronato di spine e canna in mano’ recorded by Malvasia in the Pamphili collection in Rome, as well as an Ecce Homo painted for the merchant Gnicchi. Malvasia 1678, pp. 64 and 52 respectively, cited by Pepper 1984, p. 274.

5. Both Rembrandts were sold in 1926. See B. Broos, in Great Dutch Paintings from America, exh. cat. Zwolle 1991, pp. 387-393, the former cat. no. 53, reproduced in color, and the latter reproduced p. 387, fig. 1.

6. “Old Master Paintings from the collection of Gustaf Adolf Sparre (1746-1794),” London, Sotheby’s, 5 December 2007.