21 Days of Andy Warhol is Sotheby’s three-week celebration of the essential 20th century artist with one-a-day stories and videos about Warhol’s origins, influences, inspirations, all leading up to the sale of important Warhol pieces in our Contemporary Art Evening auction 13 November.

At Sotheby’s May 2010 Contemporary Art Evening sale in New York, a rare nine-foot square self-portrait by Andy Warhol sold for a record $32.5 million. Anthony Barzilay Freund explores the artist's 20-year journey through self-portraiture, culminating in his final Fright Wig paintings, some of which were so disturbing his own dealer would not exhibit them.

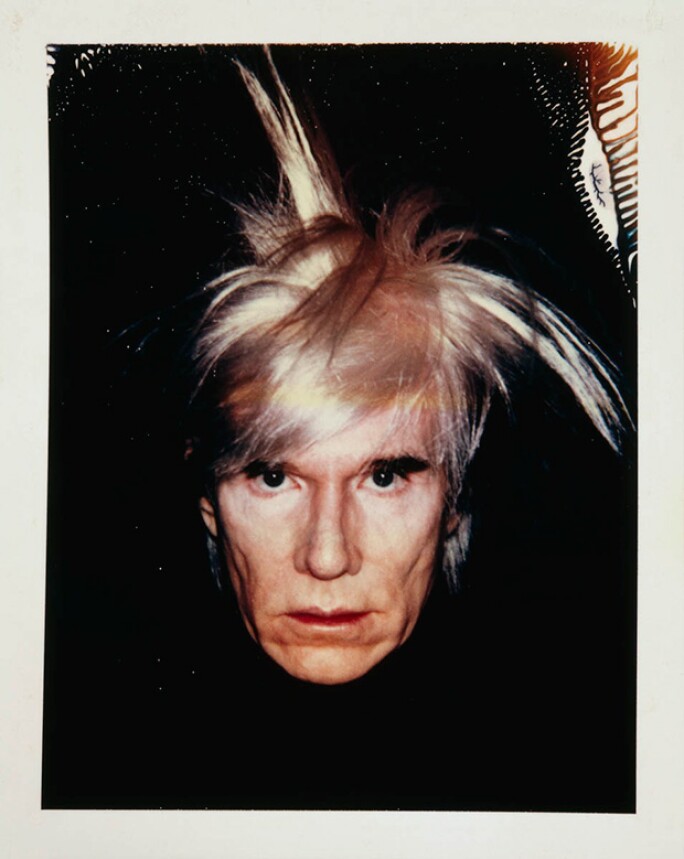

NEW YORK – From the photo-booth portraits of 1963, in which he playfully dons sunglasses and the hauteur of movie-star idols like James Dean and Marlon Brando, to the piercing, spectral self-portraits done in 1986, just months before his unexpected death at the age of 58 while recovering from routine gallbladder surgery, Andy Warhol spent a lifetime refining the image he presented to the world. On canvas and via his highly calculated public persona, he took on a mystique as compelling and complicated as those of the celebrities he photographed, silkscreened and painted. His, like theirs, is a face at once unknowable and as familiar as our own reflection. “Self-portraiture is a classic art-historical exercise and it certainly was an important element of Andy’s overall body of work,” says Vincent Fremont, a close associate of the artist throughout the 1970s and 1980s and now the exclusive agent for sales of paintings, sculpture and drawings at the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts.

Warhol was obsessed with fame and mortality in equal measure – just look at his portraits of Jackie Kennedy in mourning, Elizabeth Taylor post-tracheotomy or Marilyn Monroe, done after her suicide. But his 1963 forays into self-portraiture, at least, “are simply about creating his public persona and about his new- found celebrity,” according to Joseph Ketner, the curator of Andy Warhol: The Last Decade, that showed at the Museum of Fine Arts Houston and the Brooklyn Museum in 2010. The late art-historian Robert Rosenblum, writing in the catalogue that accompanied Andy Warhol, Self Portraits, an exhibition that travelled throughout Europe in 2004, calls these photo-booth images “pure theatre. Warhol looks like the kind of celebrity he began to frequent – masking his eyes with sunglasses, affecting poses for the invisible camera man, offering a minor cinematic narrative of undoing his shirt and tie.”

“Theatre” and “masking” are words that can be applied to much of Warhol’s public posturing during his fertile, multifaceted career. “I’m partial to him in drag and a blonde wig,” says artist Cindy Sherman, who sits on the board of the Andy Warhol Foundation and who explores issues of identity and the artistic persona in her own work. The wigs, glasses and other distinctive costumes; his inscrutable spoken script; the colourful supporting cast at the Factory; the elaborate backdrops (silver factories by day, psychedelic, smoke-filled clubs by night): they all served to enhance the artist’s celebrity while simultaneously deflecting attention from the man in the midst of this unfolding drama.

The self-portraits can be read in this light. Following the photo-booth images, Warhol’s next major series of self-portraits was done in 1964–65. In these, his fingers are covering his lips and chin in what Tobias Meyer, Sotheby’s Worldwide Head of Contemporary Art, calls “a very self conscious I-am-an-artist pose.” Indeed, Warhol was the artist of this era, at the pinnacle of the Pop-art firmament. And yet for all his fame, Fremont points out that he portrays himself “hidden in shadow.” Shadows were a recurring theme in Warhol’s work: a screenprint from his 1981 Myth series, shows him set off against a dark, jagged shadow in homage to the popular character from radio’s heyday who knew “what evil lurks in the hearts of men.” Camouflage, too, would play a prominent role in his later works. Even as Warhol is performing what can be the most self-revealing act in an artist’s repertoire, Fremont says, “he’s not going to tell you the whole story. Everyone thinks they know who he is and what he stands for, but he was very good at evading and concealing.”

Warhol would become even more guarded and elusive after surviving a 1968 murder attempt by Valerie Solanas, a deranged writer and sometime denizen of the Factory. The self-portraits “become increasingly complicated and powerful,” says dealer Irving Blum, who gave Warhol (and his Campbell’s Soup Cans) his first one-man show in 1962 at the Ferus Gallery in Los Angeles. “And I think this had a lot to do with his having been shot. I know that he went through a serious personality change. He was available and accessible before, but after the shooting he became, as you could probably guess, very protective of himself and nervous and death-fearing. And those feelings are ultimately expressed in the late Fright Wig portraits.”

Ketner says these searing portraits bring to mind Warhol’s Skull paintings of 1985, in which a monumental disembodied head floats in the dead centre of the picture plane. “Here’s somebody looking realistically at what would become his end,” he explains. “This is reflected in the paintings, which are vastly different from the earlier self-portraits.”

“If you look at the self-portraits in chronological order,” Meyer says, “they go from the examples from the early 1960s, where he sort of rushes into a photo booth and takes a photograph in an almost furtive way – he’s the sensitive, self-doubting artist – to the series where he poses with his hand in front of his face – he’s the confident, reflective artist – to the late self-portraits, for which he transforms himself into this startling icon.”

Did Warhol really have a sense of his imminent death or is that an easy reading of these darkly mesmerizing images? Fremont is not so certain. “I don’t think Andy was planning on leaving this earth, nor did any of us who worked closely with him think he wouldn’t be here. He was active and vital and focused on dozens of projects,” he says. “On the other hand, he was always a very intuitive, prophetic person. So who knows?”

Anthony d’Offay, Warhol’s legendary London dealer, tells the tale of how this remarkable series came into being: “Whenever I saw Andy, I said it would be great to do a show with you in London. And he immediately agreed and asked what I would like him to do. And I said, it isn’t for me to decide, what would you like to do? We got nowhere on several occasions along that line,” d’Offay recalls with a laugh. “I realized that it would only work if I came up with an idea that he liked. I felt it was imperative that whatever image we chose would be important and useful to his career.

“In 1985, I was in Naples spending Christmas with Joseph Beuys and his family and we visited the house of an architect where there was a large red portrait of Beuys by Warhol in the bedroom. In that second I realized that Andy really was the greatest portrait painter of the second half of the 20th century. And yet it had been a long time since anyone had seen a memorable self- portrait of his. I went immediately to see Andy in New York and put the idea to him, which he embraced warmly and said, come back in three weeks and I’ll show you a new group of photographs and together we can choose an image.

“So I came back,” d’Offay continues, “and he showed me photographs of him wearing his fright wig in various guises; there were probably about fifteen photographs. And I chose an image that was slightly less severe – the hair didn’t spike straight up; his jaw-line was a bit more filled out – than the one he preferred. That photo made me think of a death mask and I thought it would be a bad fortune for him if we used it.

“Anyway, when I got back to the Factory I found that he hadn’t actually painted the pictures from the image we’d selected, he’d chosen the more macabre one. And so I said to him, ‘Andy the paintings are absolutely great, marvelous, but they’re not the image we chose and would you please do the one we had agreed on.’ So he redid the whole show with this very beautiful, slightly milder image and the show was a huge success. The paintings were on offer at $40,000 each and we immediately sold pictures to the Metropolitan and a number of other museums all over the world. It was in every way a great commercial and critical success.”

An entry from Sunday, 13 July 1986, in The Andy Warhol Diaries, tells the artist’s side of the story: “The Show. The show. I mean, walking into a room full of the worst pictures you’ve ever seen of yourself, what can you say, what can you do? But they’re not the ones I picked. D’Offay ‘art-directed’ the whole show – he’d tell me he wanted a certain picture, and then I’d think he’d never remember, so I’d do the one I liked instead, and when he’d come back to New York he’d say that that wasn’t the one he’d picked... But he had class, he arrived at the hotel with his wife at 7:30 in the morning to say goodbye... Yeah, he was nice.”

Why was Warhol so emphatic about using what d’Offay perceived to be a more difficult image, which was certainly less flattering to the sitter? “Warhol was always conscious of his looks; he’d had an operation on his nose to make it less broad and he was self- conscious about losing his hair,” says Meyer. “But in this portrait he turns the loss of his hair into an expression of the hair. And he seems to have forsaken vanity, which is what great artists do when they’re confident enough,” Meyer continues. “It’s a little bit like Rembrandt’s last self-portraits. Here was someone who was extremely vain and obsessed, too, with outward appearance. But the late portraits are of a man who is dissolving in front of your very eyes.”

And like Rembrandt’s final self-depictions, Warhol’s 1986 Fright Wig paintings have become the defining image for the artist. “It’s ironic because during his lifetime Warhol enjoyed the peak of popularity in the 1960s,” says Ketner. “But when you ask somebody about their image of him, this is what they conjure, not the guy in the Factory.”

“I’d say he definitely got more into his own myth as he got older and into presenting himself in the same glamorous manner he presented everyone,” Sherman says. “And then as he got even older he abstracted himself more.”

From the guy in the photo-booth and the Factory to the art-world elder statesman who, perhaps, is contemplating his own mortality, Warhol’s self-portraits stand out in an unparalleled body of work. “The portraits were another way Andy was a great innovator,” d’Offay concludes. “He used photographs and found images and repeated images and the way paint is affected by chance. And in a sense he got his subjects to paint themselves using the simplest possible materials and as little interference as possible from him. I think it’s this use of the raw materials and the photographer’s split-second understanding of who someone is that makes these works so iconic.”

Tomorrow: Andy and the First Million-Dollar Warhol at Sotheby's