- 6

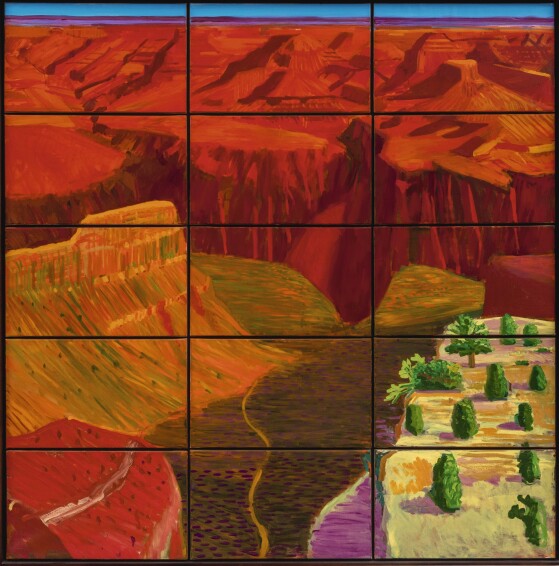

David Hockney

Description

- David Hockney

- 15 Canvas Study of the Grand Canyon

- oil on canvas, in 15 parts

- overall: 169 by 166.5 cm. 66 1/2 by 65 1/2 in.

- Executed in 1998.

Provenance

Acquired from the above by the present owner in 1999

Exhibited

London, Tate Britain, David Hockney, February - May 2017, p. 167, illustrated in colour

Literature

Condition

"In response to your inquiry, we are pleased to provide you with a general report of the condition of the property described above. Since we are not professional conservators or restorers, we urge you to consult with a restorer or conservator of your choice who will be better able to provide a detailed, professional report. Prospective buyers should inspect each lot to satisfy themselves as to condition and must understand that any statement made by Sotheby's is merely a subjective, qualified opinion. Prospective buyers should also refer to any Important Notices regarding this sale, which are printed in the Sale Catalogue.

NOTWITHSTANDING THIS REPORT OR ANY DISCUSSIONS CONCERNING A LOT, ALL LOTS ARE OFFERED AND SOLD AS IS" IN ACCORDANCE WITH THE CONDITIONS OF BUSINESS PRINTED IN THE SALE CATALOGUE."

Catalogue Note

The American West has long served as an indelible symbol of American national pride and identity, immortalised in creative arts from Thomas Moran’s paintings to John Steinbeck’s literary odysseys. It is the land of opportunity, the beacon of the American Dream. The very concept of manifest destiny, a doctrine that held that the westward expansion of the United States was not only inevitable but divinely endorsed, found its symbolic equivalent in the Grand Canyon. Towering cliffs reaching over a mile high drop precipitously down to the Colorado River below. For over two hundred and fifty miles the water wends its way through this imposing landscape, culminating in a lake just outside Las Vegas, on the border of California, the promise land of the Gold Rush. For many painters the spiritual connotations of this landscape, and its status as the epitome of the American Sublime, are pervasive.

Ostensibly, the Grand Canyon paintings were something of a departure for Hockney. He had spent much of 1997 in his home county of Yorkshire, visiting his mother and his friend Jonathan Silver, whose terminal illness provided tragic impetus for Hockney to remain in the area. As a result, Hockney began a series of large scale paintings of the Yorkshire landscape, such as Garrowby Hill and Road Across the Wolds. Lush, green, and somewhat provincial, these paintings seem a far cry from the fierce reds, oranges, and purples of the present work. The colours themselves are chosen to evoke a very direct sense of place: these reds could not be found anywhere other than at the Grand Canyon, just as the greens could only be seen in the Yorkshire hills. Despite this apparent divergence, the works are bound both stylistically, with their concern for spatial depth and use of colour, and thematically, with the newly emergent spirituality of Hockney’s practice. Indeed, Laurence Weschler, a regular interviewer of the artist, identified the impetus for Hockney’s paintings of the Grand Canyon and of Yorkshire as a subliminal response to the deaths of many of his friends during the AIDS crisis in the 1980s and early 1990s. The artist’s paintings of flowers have often been interpreted as responses to these tragedies, but Weschler proposed that with landscape “you keep returning to magnificence and awe and – might the proper word be reverence? – as responses to all this devastation” (Laurence Weschler in conversation with David Hockney, in: Exh. Cat., L.A. Louver, Los Angeles, Looking at Landscape/Being in Landscape, p. 6). After all, there is a definite human dimension to these paintings that purport to be desolate depictions of landscapes. The techniques that Hockney uses all revolve around the perspective of the spectator who stands in the centre of the composition. Indeed, Hockney said of these works that his intention was to “convey the experience of space” (David Hockney cited in: Laurence Weschler, ‘Wider Perspectives: Painting Yorkshire and the Grand Canyon (1998)’, True to Life: Twenty-five Years of Conversations with David Hockney, Berkeley, 2008, p. 112). However, as Chris Stephens, the curator of Hockney’s 2017 Tate retrospective, notes, there is a definite degree to which these works are “positioned in relation to a different register of the human experience”, that is, a spiritual sphere (Chris Stephens, ‘Experiences of Place’, in: Exh. Cat., London, Tate Britain, David Hockney, p. 163). Hockney seems to accept this idea of spirituality. In the same interview with Weschler he responded: “A friend of mine looked at [the Grand Canyon painting] and said he thought he was on the way to Heaven, as he put it. A very nice thing to say really. My sister thinks space is God, and I’m like that” (David Hockney in conversation with Laurence Weschler, op. cit., p. 31).

Hockney first began the Grand Canyon paintings after a series of drives between Santa Fe and Los Angeles. Impressed by the vast emptiness of the West, Hockney’s intensely associative mind began to draw parallels between the landscape he had painted in Yorkshire, and the rugged terrain he saw before him. Both were largely unpopulated – Hockney said of the areas he visited in Yorkshire that “not many people live here” – and offered panoramic views that seemed, at least in Yorkshire, out of place in a densely populated country (David Hockney, cited in: Chris Stephens, op cit., p. 161). This stimulus was compounded by Hockney’s visit to a retrospective exhibition of Thomas Moran’s work, an artist famed for his epic depictions of the Grand Canyon. Moran is an artist who Hockney admires and feels tied to, given that, in Hockney’s words, he had been born “exactly a hundred years before me not forty miles away from Bradford”, Hockney’s own birthplace, and had subsequently emigrated to the United States (David Hockney in conversation with Laurence Weschler, op. cit., p. 112).

Despite these similarities, Hockney’s interest in depicting the experience of space should not be confused with Moran’s interest in topography and Turner-esque stylistic flourishes. Unlike Moran, whose spirituality elevates landscape to a plateau above human comprehension, Hockney’s paintings channel the awesome power of nature, rather than an implication of divine intervention. As Hockney said when the landscapes were first shown, the Grand Canyon is “the biggest place you can look out over that has an edge” (Ibid., p. 28). As such, it presents an enormous challenge to painters; indeed, during one of his roadtrips, Hockney came across an old advertisement for the Santa Fe railroad that described the Canyon as “the despair of the painter”, which quite naturally he interpreted as a challenge (Chris Stephens, op. cit., p. 161).

The resultant paintings are dizzyingly immersive. Recalling nineteenth-century panoramas and Monet’s curved Nymphéas canvases at the Orangerie in Paris, the viewer is obliged to move around in order to take them in. Hockney addressed the task of painting on this scale in a fashion analogous to Constable when he was working on his famous ‘six-footers’. Working from sketches made on site, he prepared a careful drawing of the composition and then a small series of large scale paintings, including the present work. However, instead of creating the works on a single, huge canvas, Hockney adopted a new device that solved the impracticalities of working in such gigantic proportions whilst simultaneously invoking art historical associations with Modernism and American Minimalism. This device consisted of using multiple small canvases assembled in groups of as many as 60. Not only was this intensely liberating, as it allowed Hockney to extend his canvas with minimal effort, but it created a grid-like framework, the most recognisable motif of the austere work of Piet Mondrian, Donald Judd, and Carl André. Rosalind Krauss described the grid in 1979 as “a structure… emblematic of the modernist ambition with the visual arts” (Rosalind Krauss, ‘Grids’ The Originality of the Avant-Garde and Other Modernist Myths, Cambridge, Mass., 1985, pp. 10-22), but in the context of Hockney’s exuberant painting, which flies in the face of all the anti-mimetic theories of both groups, the usage of the grid “proffers a wry commentary on the demise of Modernism” (Tim Barringer,’Seeing with Memory: Hockney and the Masters’, in: Exh. Cat., London, Royal Academy of Arts, David Hockney: A Bigger Picture, 2012, p. 51).

Quite aside from showcasing Hockney’s renewed engagement with nature, spirituality, and art history, these works demonstrate his fundamental understanding of his adopted homeland. Quite aside from the associations of the West with ideas of American exceptionalism and manifest destiny, it is fundamentally connected to the fantasy of the outlaw. From cowboys to hippies to biker gangs, material iterations of the freedom that constitute the basis of America’s self-image have always been associated with the Outback and the West in general. America styles itself as the land of individual freedom, and the vast lawless zone in the west of the country is the arena where this liberty can be enjoyed. Before he even arrived in Los Angeles in 1964, Hockney had begun to paint images of Los Angeles “as a landscape of pleasure, a bacchanalian arcadia of sexual freedom” (Tim Barringer, op. cit., p. 46). As a gay artist growing up in the north of England Hockney felt ostracized. He, like many others, considered L.A. to be a Mecca for the gay community, an idea bound up not only with the actual sexual liberation of California, but the pervasive idea of the individual liberties enjoyed by Americans. Although many of the illusions surrounding the myth of the renegade American have been laid bare by the work of artists such as Richard Prince with his Cowboy series, there is a lingering appeal to the vast unpoliced expanses of the American desert. Hockney’s Grand Canyon paintings tap into this notion of liberty, and harness the symbolic weight of the American desert as an icon of freedom.

Born of Hockney’s immersion in American culture and his turn towards landscape at the end of the millennium, 15 Canvas Study of the Grand Canyon stands at the forefront of the artist’s output. Bound up in notions of spirituality following the death of his friends, as well as a self-reflective meditation on the artist’s own position as an outsider, this work possesses a searing humanity despite the absence of human figures. The wry joke at Modernism’s expense is entirely in-keeping with Hockney’s cheeky disposition, and the colours, cacophonous and vibrant, with the light yellow of the foreground giving way to the deep red of the mountains, heightened still further by the strip of blue across the top of the composition, are among the most exciting and alive of the artist’s opus. Steeped in history, both social and artistic, 15 Canvas Study of the Grand Canyon is a masterpiece that represents the very best of Hockney’s work.